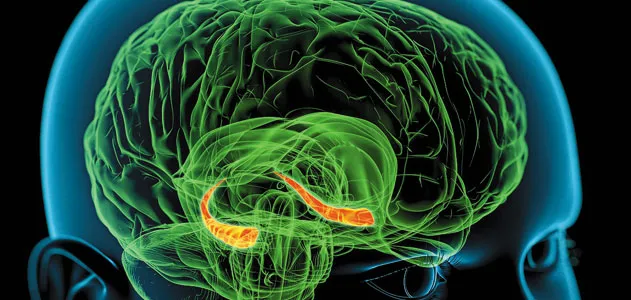

In 2013, he published his findings in Science: that up to 60% of the neurons in the hippocampus (known for learning and memory) shut off in VR. What he learned quickly was that even his lab’s own VR system-which puts a mouse on a miniature treadmill surrounded by immersive screens-is not so real to the brain at a structural level. To unpack how the brain works, he began putting mice into extremely complex, tiny virtual reality rigs. He believed that, with this common entry point between physics and neuroscience, he could begin to deconstruct the mechanisms of the brain. Much like light and sound waves across the universe are just harmonic frequencies playing out across space, so too is human thought powered by the oscillation of energy passing from neuron to neuron. Mehta is a physicist by training, but he has been studying the brain for nearly two decades. He’s arguing that something within VR itself-or at least the VR system his lab has built for the mice he studies-can impact the brain at a deep, electrical level, which could impact treatment and learning separately, and on top of VR’s intense visual simulations. Mehta isn’t demonstrating that VR can have positive effects on the brain just because it feels like real life. We know that these headsets-for whatever mainstream market appeal that’s lacking-have proven to be an excellent way to re-create a certain sensation, or offer a particular stimulus, within the tight confines of hospital beds. In truth, VR is already being used for all sorts of treatments, ranging from its clinical use for PTSD (post-traumatic stress disorder) to physical rehabilitation. Their findings were published in Nature Neuroscience. But now, for the first time, scientists at the University of California, Los Angeles, have found a way to increase theta rhythms in mice simply by putting them inside a virtual reality simulation. In more than 70,000 studies and counting, theta rhythms have been shown to be critical in cognition, learning, and memory, and we see them go awry in maladies like Alzheimer’s disease, ADHD (attention deficit hyperactivity disorder), anxiety, and epilepsy.įor years, drugs have attempted to boost theta rhythms by attaching themselves to neurons in our brain, with varied success. They disappear when we sleep but crop back up when we dream. Theta rhythms are active when we’re awake, then increase when we walk. And the theta is the most prominent rhythm in the brain. For more than 70 years, scientists have known about a brain phenomenon called the “theta rhythm.” To oversimplify it, your brain thinks not just in frequencies but in syncopated beats.

0 kommentar(er)

0 kommentar(er)